Teenagers Kill Cyclist in Albuquerque—Did Social Media Inspire Another Deadly Attack?

Follow us on

social media!

Update – March 27, 2025: Since the original publication of this article, all three suspects involved in the May 2024 murder of cyclist Scott Habermehl have been taken into custody.

The 13-year-old driver, Johnathan Overbay, 15-year-old passenger William Garcia, and 11-year-old recorder of the incident, Messiah Hayes, are all now facing murder-related charges. New court records also reveal that the teens showed the video to classmates and had a history of other violent crimes. Details of their arrests, prior criminal behavior, and court proceedings have been added to this article.

Violence Without Reason: When Teenagers Kill for Attention

A shocking and senseless crime has shaken the Albuquerque cycling community. On May 29, 2024, three juveniles—ages 13, 15, and 11—stole a car and intentionally ran down a cyclist commuting to work. Their victim, 63-year-old Scott Dwight Habermehl, was riding in a designated bike lane when the young driver accelerated directly into him, killing him instantly.

The case remained unsolved for months—until a disturbing video resurfaced online in early 2025. The footage, recorded from inside the stolen car, showed the teens plotting the attack, laughing, and fleeing the scene. This evidence ultimately led to the arrest of the 13-year-old driver, Johnathan Overbay, while his 15-year-old accomplice and 11-year-old passenger remain at large.

This isn’t the first time a teen-driven, deliberate hit-and-run against a cyclist has been caught on camera. Less than a year earlier, in Las Vegas, two teenagers filmed themselves killing retired police chief Andreas Probst in a stolen car. Weeks later, a teen driver in Huntington Beach, California, embarked on a hit-and-run spree targeting cyclists, killing 70-year-old Steven Gonzalez.

Is this a disturbing new crime trend? Are viral videos glorifying these attacks and inspiring copycat killings? And most importantly—what is pushing teenagers to commit such brazen acts of violence?

Albuquerque Cyclist Murder Case:

How Social Media May Have Fueled a Murder—Then Helped Uncover It

At 4:40 a.m. on May 29, 2024, Scott Habermehl was cycling to work at Sandia National Laboratories when a stolen vehicle swerved into the bike lane and struck him at full speed. The driver, 13-year-old Johnathan Overbay, was encouraged by 15-year-old William Garcia to "just bump him." Instead, Overbay sped up, hitting Habermehl head-on.

The boys fled the scene, laughing as Habermehl lay dying on the pavement. With no security footage or immediate witnesses, police struggled to identify the suspects, and the case went cold for months.

Then, in February 2025, an anonymous tipster alerted police to a shocking video circulating on Instagram. Around the same time, a middle school principal also contacted authorities after a student flagged the disturbing footage.

The Video That Led to an Arrest

Investigators obtained search warrants and retrieved multiple video clips from phones seized in a separate case. The footage showed the teens identifying Habermehl by his flashing bike light and laughing about hitting him. The 11-year-old in the front passenger seat waved a handgun before ducking as the impact occurred.

On March 18, 2025, Overbay was arrested and charged with:

- Murder

- Conspiracy to commit murder

- Leaving the scene of an accident involving great bodily harm or death

- Unlawful possession of a handgun by a minor

As of March 27, 2025, all three suspects—Johnathan Overbay (13), William Garcia (15), and Messiah Hayes (11)—have been arrested. Each faces varying degrees of murder-related charges. Prosecutors confirmed the teens showed the video to classmates after the killing.

Where Are the Suspects Now?

As of late March 2025, all three juveniles involved in the deliberate killing of Scott Habermehl have been arrested and face charges.

13-Year-Old Johnathan Overbay

- Believed to be the driver.

- Faces charges of first-degree murder, conspiracy to commit murder, leaving the scene of an accident, and unlawful carrying of a handgun.

- In court, prosecutors described him as a danger to the community and revealed he committed other crimes in the weeks leading up to the crash, including breaking into a school, assault, and allegedly firing a weapon at a building the day of the murder.

- Judge Catherine Begaye ordered him to remain in custody.

15-Year-Old William Garcia

- Arrested on March 26, 2025.

- Faces an open count of murder, conspiracy, leaving the scene, and unlawful handgun possession.

- Identified in the video as the voice encouraging Overbay to “just bump” the cyclist.

11-Year-Old Messiah Hayes

- Allegedly filmed the crime and brandished a handgun in the video.

- Arrested earlier in 2025 on unrelated charges and taken into state custody again on March 25.

- Now faces a murder charge, though New Mexico law prevents juveniles under 12 from being held in a juvenile detention facility.

- Authorities say Hayes has a prior criminal history involving burglary, vandalism, and organized retail theft.

Prosecutors revealed that the boys showed the video to classmates, further alarming school officials. Albuquerque Public Schools confirmed that both Overbay and Garcia were enrolled in the district; Hayes was not.

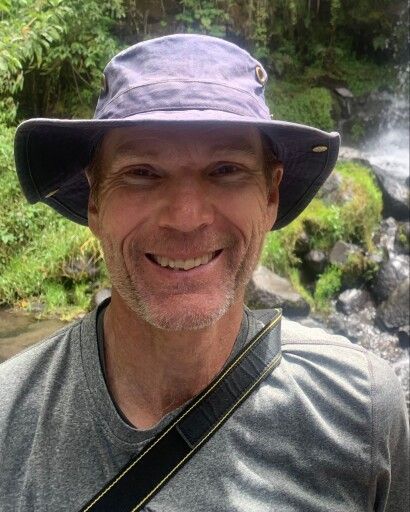

Who Was Scott Habermehl? A Life Cut Short by Senseless Violence

Scott Habermehl was a dedicated scientist, loving husband, father, and outdoor enthusiast. Born in Perry, Iowa, in 1960, he earned a Ph.D. in physics and built a remarkable career at Sandia National Laboratories, where he contributed to advancements in thin film and semiconductor engineering. His work had a lasting impact on radiation-hardened technology used for national security and space applications.

Beyond his career, Scott was a devoted family man who found joy in hiking, biking, skiing, and spending time with his wife and two sons. He was known for his humility, generosity, and deep appreciation for nature. Just before his passing, he had built a home in Leadville, Colorado, where he planned to share his love for the mountains with family and friends.

His tragic murder has left an irreplaceable void in the lives of those who knew and loved him.

A Disturbing Pattern: Teens Killing Innocent Cyclists

The Albuquerque case is not an isolated incident. It mirrors other deadly attacks on cyclists involving teenage drivers, stolen cars, and recorded footage shared online.

Las Vegas: The Murder of Andreas Probst (August 14, 2023)

- 64-year-old retired police chief Andreas Probst was cycling near his home in Las Vegas, Nevada, when two teenagers deliberately ran him over in a stolen Hyundai.

- Like the Albuquerque case, the murder was filmed from inside the vehicle and later posted on social media.

- In the video, the passenger laughs and encourages the driver to hit Probst, just as in the Albuquerque footage.

📖 Read more: Teens Target Cyclists in Hit-and-Run Murders of Andreas Probst and Steven Gonzalez

Huntington Beach: A Teen Driver’s Hit-and-Run Spree (September 10, 2023)

- A teen driver struck three cyclists in a 45-minute span, killing 70-year-old Steven Gonzalez.

- The suspect was arrested driving a damaged black Toyota Camry, which had been used to target cyclists deliberately.

📖 Read more: Teen Arrested for Hit-and-Run Spree Targeting Cyclists

The parallels between these crimes are chilling:

- Teen perpetrators

- Stolen vehicles used as weapons

- Violence recorded and shared on social media

- Lack of clear motive beyond thrill-seeking

- Callous disregard for human life

Are these murders part of a disturbing trend fueled by social media? Did the viral Las Vegas hit-and-run video inspire copycat crimes? Or are we witnessing the rise of a new form of thrill-killing, where cyclists are seen as easy targets for violence?

These cases demand more than just arrests—they require a deeper examination of how social media, teenage impulsivity, and a broken justice system may be contributing to these senseless acts of violence.

New Mexico’s Juvenile Justice System and the Failure to Reform

In New Mexico, the juvenile justice system has specific statutes for prosecuting minors, particularly in serious cases like murder. Teens aged 15 to 18 charged with first-degree murder can be classified as "serious youthful offenders," meaning they are automatically tried as adults and face adult sentencing if convicted.

For other violent crimes, juveniles aged 14 and older may be designated as "youthful offenders," allowing a judge to decide whether they should face adult sentencing.

However, children under 14, like Johnathan Overbay, the 13-year-old charged in this case, fall under the juvenile system, which has far more lenient sentencing guidelines. Even for the most violent offenses, the maximum confinement for a juvenile under 14 is until the age of 21, after which they must be released. This legal gap means that, despite intentionally killing an innocent cyclist, Overbay cannot be charged as an adult under current law.

House Bill 134: The Failed Attempt to Close Legal Loopholes

In 2025, House Bill 134 aimed to reform New Mexico’s juvenile justice system by amending the Delinquency Act and the New Mexico Children's Code to hold young violent offenders more accountable. The bill proposed lowering the age threshold for adult prosecution from 15 to 14 for serious crimes, including murder.

Supporters argued that current laws allow dangerous offenders under 15 to receive minimal sentences, even for the most heinous acts. The bill had bipartisan sponsorship and was seen as a necessary step toward closing legal loopholes that let juveniles avoid adult penalties for violent crimes.

However, on March 6, 2025, House Bill 134 was effectively killed when the House Consumer & Public Affairs Committee (CPAC) voted 4-2 along party lines to table the measure, preventing it from moving forward.

How Committee Members Voted on HB 134

Voted to Table (Effectively Killing the Bill):

- Representative Joanne J. Ferrary (District 37, Democrat) – Chair

- Representative Angelica Rubio (District 35, Democrat) – Vice Chair

- Representative Andrea Romero (District 46, Democrat) – Member

- Representative Elizabeth “Liz” Thomson (District 24, Democrat) – Member

Voted Against Tabling (Supported Harsher Penalties for Juvenile Offenders):

- Representative John Block (District 51, Republican) – Member

- Representative Stefani Lord (District 22, Republican) – Member

Without legislative reform, juveniles like Johnathan Overbay—who, at just 13 years old, committed an intentional murder—will continue to be shielded from adult prosecution. As the law stands, he cannot face the same level of punishment as an adult murderer, no matter how violent or premeditated the crime.

Another Legislative Failure: The Juvenile Corrections Act Dies in the Senate

In the weeks following the arrest of all three teens accused of murdering cyclist Scott Habermehl, New Mexico lawmakers were presented with another opportunity to address juvenile crime. But once again, the proposed reform fell short.

On March 20, 2025, the New Mexico Senate held a hearing for House Bill 255, known as the Juvenile Corrections Act. The bill aimed to modernize and strengthen the state’s outdated juvenile justice laws, which have not been significantly amended since 1993.

The measure proposed:

- Extending the length of probation from 90 days to

6 months for released youth offenders

- Allocating

$6.1 million toward rehabilitation and programming

- Granting

district court judges more discretion in sentencing

- Allowing for a broader review of New Mexico's

Children’s Code

Despite bipartisan sponsorship and growing concern over youth violence—including the highly publicized arrests of Johnathan Overbay (13), William Garcia (15), and Messiah Hayes (11)—the bill failed in a 13-24 vote just after midnight on March 21.

Political Divide Over Juvenile Justice

Supporters, including Democratic Sen. Antonio “Moe” Maestas, expressed frustration that lawmakers were unwilling to compromise on a bill aimed at accountability and rehabilitation.

Meanwhile, some Republican lawmakers said the bill wasn’t strong enough.

Sen. Nicole Tobiassen, who voted against the measure, argued it lacked mandatory provisions for mental health treatment during detention and probation.

Missed Opportunity for Reform

With HB 255 now shelved, New Mexico remains without updated juvenile sentencing laws or mental health mandates for youth offenders. Lawmakers on both sides acknowledged the system is broken—but disagreed on how to fix it.

Some are now calling for a special session to revisit juvenile justice reform. Whether that happens remains to be seen.

For now, juveniles like Overbay and Hayes—both under 14—remain shielded from adult sentencing, even in cases involving deliberate and violent murder.

Do Stricter Punishments Change Criminal Behavior?

With House Bill 134 dead, New Mexico’s juvenile justice system remains as it was—offering limited pathways for prosecuting violent youth offenders as adults. But even if harsher penalties were in place, would they truly deter crimes like this?

The core issue may not be the punishment itself but rather a deeper societal shift. Today’s youth are immersed in a culture of instant gratification, where attention—good or bad—is often the ultimate reward. Social media glorifies shocking content, making it easy for teenagers to chase notoriety without fully grasping the irreversible consequences of their actions.

Do they understand the law? Do they comprehend what taking a life truly means? Or are they so desensitized to violence that murder has become just another form of entertainment?

Scott Habermehl, Andreas Probst, and Steven Gonzalez were all killed by teenage drivers in calculated, intentional attacks. Each time, the perpetrators laughed as they fled. Each time, a stolen car became a weapon. Each time, another cyclist lost their life in a horrifying trend.

Without meaningful change—whether in the justice system, parental oversight, or the way we allow social media to shape young minds—how many more will follow?

Preventing Future Violence Against Cyclists

Preventing future tragedies requires a multifaceted approach that addresses the root causes of these violent crimes. It demands changes in infrastructure, education, law enforcement, and community awareness to ensure that cyclists are no longer seen as easy targets.

- Stronger Juvenile Sentencing Laws – Closing loopholes that allow violent minors to receive minimal sentences.

- Social Media Accountability – Cracking down on violent content that glorifies attacks.

- Community Intervention & Parental Oversight – Addressing youth desensitization to violence.

- Cycling Infrastructure Improvements – Expanding protected bike lanes to reduce vulnerability.

- Stricter Traffic Enforcement – Ensuring that reckless and violent drivers are held accountable.

📖 Read more: What Happens When You Hit a Cyclist with Your Car

Bike Legal: Advocating for Cyclists’ Rights Nationwide

The families of Scott Habermehl, Andreas Probst, and Steven Gonzalez deserve justice. Their tragic deaths serve as painful reminders of the dangers cyclists face on the road and the urgent need for reform.

At Bike Legal, we stand with cyclists and their families in the fight for safer roads. As a national law firm dedicated exclusively to representing cyclists, we not only provide legal representation for victims of bicycle crashes but also work to educate the public on cyclists' rights and responsible road-sharing. Our mission is to ensure accountability for reckless drivers and push for stronger protections for cyclists across the nation.

If you or a loved one has been impacted by a cycling accident, visit Bike Legal to learn more about your rights and how we can help.

877-BIKE LEGAL (877-245-3534)

FAQ’s

Q: Why are teenagers deliberately running over cyclists?

A: There is growing concern that social media and viral videos may be glorifying hit-and-run attacks on cyclists, inspiring copycat crimes. Cases in Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and Huntington Beach all involve teenagers using stolen cars as weapons, recording the murders, and sharing them online. Experts suggest that some young offenders are desensitized to violence, seeking social media notoriety, or engaging in thrill-seeking behavior without fully understanding the consequences.

Q: Can teenagers be charged as adults for murder in New Mexico?

A: In New Mexico, only minors aged 15 and older can be automatically tried as adults for first-degree murder. Those under 14, like 13-year-old Johnathan Overbay, fall under the juvenile system, where the maximum sentence is confinement until age 21. This means that, despite deliberately killing Scott Habermehl, Overbay cannot receive an adult sentence. Efforts to change this law, such as House Bill 134 (2025), were voted down.

Q: How can cyclists protect themselves from targeted attacks?

A: While these incidents remain rare, cyclists can take extra precautions to reduce risk:

- Use well-lit bike routes and avoid riding alone in isolated areas at night.

- Install front and rear cameras on your bike to record any dangerous behavior.

- Report any suspicious vehicles following or harassing cyclists to authorities.

- Stay aware of your surroundings and have an emergency plan if confronted with aggressive drivers.

- Advocate for better cycling infrastructure and stronger legal protections for vulnerable road users.